Is the stock market really in an "AI bubble"?

By Mattia Landoni and Renxuan Wang

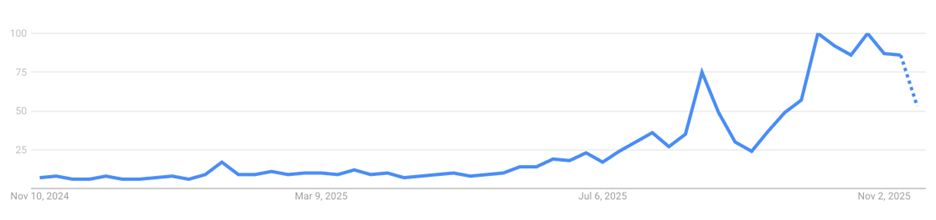

There has recently been growing buzz about the possibility of an AI bubble. Google search interest for “AI bubble” (Exhibit 1) has climbed markedly, and most major outlets have now offered their own think pieces on the topic: Financial Times, Wall Street Journal, Economist, Brookings, and even the New York Times. On the investor side, prominent figures such as Ray Dalio and Michael Burry (of The Big Short fame) have expressed variants of the bearish case that AI-related firms are overpriced.

Exhibit 1. AI bubble: interest over time (Google Trends)

For now, they have not been proven right. Dalio articulated his concerns early in the year, long before the market rallied further; by the time Burry’s short positions in NVIDIA and Palantir became public through delayed regulatory disclosures, his fund had already been wound down. In closing the fund, he lamented that his “estimation of value” was “not in sync with the markets”.

None of this discredits them as investors. Market timing is notoriously difficult; some say it is like catching a falling dagger — even if you do, you may still get hurt. Even those that are ultimately proven right often suffer for being early. Michael Burry, famous for predicting the 2007 subprime collapse, endured deep mark-to-market losses before being vindicated. Julian Robertson correctly foresaw the tech bubble in the late 1990s, but closed his fund just before it burst. One of the authors of this piece learned the same lesson early: as a new high-school graduate, he invested what was then a personal fortune in a single internet stock, just in time for the Dot-com crash to erase almost all of it.

Because market timing is so difficult, the debate over an “AI bubble” has produced a flood of data-driven analyses that frequently reach conflicting conclusions. Two influential reports published in London on the same day took opposite positions: the Bank of England warned of elevated downside risk in equities, while Goldman Sachs International cheerfully reassured us that we are not in a bubble (yet). Rather than add to the cacophony, we will endeavour here to find a common thread within existing arguments and offer a framework through which any new data can be interpreted.

A key distinction runs through the debate: the difference between investors pricing AI optimistically and firms investing in AI infrastructure optimistically. These are logically separate claims. As Warren Buffett famously put it, “a too-high purchase price for the stock of an excellent company can undo the effects of a subsequent decade of favorable business developments”.

Are AI stock prices, or all stock prices, too high?

Most observers agree that equity prices in general are high, including both tech and non-tech. Goldman Sachs estimates that the long-run dividend growth implied by current prices is implausibly high, but still below historical bubble extremes such as the Dot-com episode in 2000 or the “Nifty Fifty” era in the 1960s. By this measure, valuations are elevated but not obviously irrational.

A more familiar metric, the price-to-earnings (P/E) ratio, tells a similar story. The US S&P 500 currently trades at a high multiple relative to its history (20-25, depending on source). Surprisingly, however, the S&P 500 excluding Big Tech trades at even more extreme multiples. Other major equity markets show similar patterns. Taken together, this evidence suggests that high valuations cannot be explained purely by enthusiasm for AI. They also reflect the macroeconomic environment: low real interest rates, ample liquidity, and moderate inflation—a condition that favors firms with fixed-rate debt and pricing power.

Are AI infrastructure investments large enough to influence pricing?

Yes. Estimates for 2025 data-center and AI-infrastructure investment range from roughly $260 billion to $400 billion. To put this in perspective, the “Big Seven” US tech firms (Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Nvidia, and Tesla) collectively generate roughly $2 trillion in annual revenue. Thus, sector-wide AI-infrastructure capex corresponds to about 13–20% of Big-Seven revenue.

At the firm level, the numbers are even starker. Microsoft’s 2025 guidance appears to point to $80–120 billion of infrastructure capex, equal to roughly 33–50% of its 2024 revenue. Amazon’s capex is widely projected around $100 billion, equivalent to about 16% of revenue. Alphabet is expected to spend $85–90 billion—around 25% of its revenue—while Meta’s capex guidance stands near $70 billion, or roughly 40–45% of its 2024 revenue.

Are firms over-investing?

Given the unprecedented size of current AI capex, a natural question is whether firms are over-investing. Historically, technological revolutions naturally induce systematic uncertainty and learning, generating apparent “bubbles” that can only be recognised after the fact. AI shows several features consistent with that pattern, such as low predictability and rapid diffusion. Even so, established, highly profitable firms almost never invest at this intensity in new general-purpose technology. Railroads in the 19th century were enormous national investments, but not typically undertaken by mature, profitable giants. The 1990s fiber-optic boom is the closest analogy, but even then, telecom incumbents invested a smaller fraction of revenue. The scale of today’s AI build-out is, in this sense, unprecedented.

One widely circulated critique is Harris Kupperman’s back-of-the-envelope calculation. He starts with an estimated $400 billion of AI-related capex in 2025. Using an assumption of 10-year economic life for data-center assets, he derives $40 billion (= 400 / 10) in annual costs from depreciation. This is a generous assumption. For context, consider that estimates of chip life fall in the three-six years range in debates about GPU obsolescence. Even so, those costs are roughly double current AI-related revenues, estimated around $15–20 billion. Even assuming a generous 25% gross margin, break-even requires scaling AI revenues to $160 billion per year. To generate a solid return on invested capital, revenue would need to reach $400–500 billion. And that is just for one year’s investment. If 2026 capex matches or exceeds 2025 levels, as many expect, the implied future revenue runs into the trillions.

On the other side of the debate is the “infinite demand for compute” view. JPMorgan recently projected $5 trillion in global AI-infrastructure spending over the next five years, arguing that demand for computing power remains “astronomical.” The bank appears to be backing its conviction through financing: it is reported to be arranging or participating in several multibillion-dollar data-centre financing deals (including a $38 billion package for Oracle). In addition, physical constraints such as electricity, water, and data infrastructure, supply chain bottlenecks, and zoning may naturally limit overbuilding. These constraints could mean that even if current investments overshoot optimal levels, the error may be capped simply because building overcapacity is physically hard.

What conclusions can we draw?

AI-infrastructure investments are large, speculative, and, by historical standards, unprecedented for firms of this size. They carry significant execution risk. Yet the firms undertaking them are exceptionally well capitalised, generally well managed, and operating under physical and regulatory constraints that may help prevent catastrophic overinvestment. It is plausible that tech firms are priced highly despite investor skepticism about their AI capital spending—rather than because the market has fully embraced it.

Advice for investors

Whether valuations reflect AI optimism or broader macro forces, investors should not rush to take a short position against the tech index, or the broader stock index. Risk assets everywhere are priced richly; the AI sector is not an outlier. As always, it is recommended to evaluate firms on a case-by-case basis. If you are really worried about the bubble burst scenario, diversify. If the author’s Dot-com-era investment mentioned earlier had gone into an S&P 500 index fund rather than a single speculative stock, it would now be up about 400%—meaning an almost 7% annualised return despite buying at the worst possible moment. And for even more diversification, consider a broader index, including Chinese or emerging-market equities.

Advice for policymakers

This is largely an equity-financed boom, which limits systemic risk. Equity-financed technology booms can contribute positively to long-run innovation, even if valuations eventually correct. That said, if JPMorgan’s projections are right, a non-trivial wave of debt-financed infrastructure investment—perhaps on the order of $1.5 trillion—could follow, which warrants careful monitoring.

Mattia Landoni is Associate Professor of Finance at CEIBS. Renxuan Wang is Assistant Professor of Finance at CEIBS. In July 2026, they will co-teach Investments for CEIBS' Finance MBA programme.