Is ‘Be Yourself’ Always the Best Advice?

By Emily M. David, Tae-Yeol Kim, Jiing-Lih (Larry) Farh, Xiaowan (Lucy) Lin, and Fan Zhou

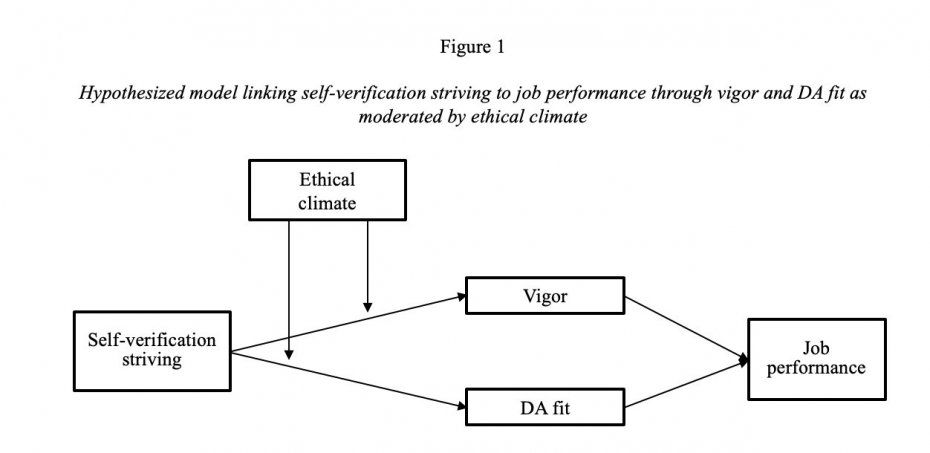

Although we know that individuals who tend to reveal their true selves to others at work are better performers, little is known about why this is the case or in which workplace environments this trait will be most helpful. One factor which might play a role in shedding lighting on employee performance is self-verification (i.e., the confirmation of oneself). Self-verification theory proposes that people are generally motivated to act in alignment with their true selves in order to maintain both cognitive symmetry and stable interpersonal relationships, where high self-verification strivers value self-verification more than those who are low, and tend to consistently self-verify at higher levels.

Furthermore, it is worth examining the intervening mechanisms through which self-verification striving relates to job performance. Two such potential mechanisms are vigour (i.e., an affective state characterised by liveliness and energy) and demand-ability (DA) fit (i.e., the match between an employee’s knowledge, skills, and abilities and job requirements).

High self-verification strivers likely waste fewer unnecessary resources than those who are constantly trying to either pretend to be someone they are not or make themselves unknowable. Energies, in particular, are important internal resources that are used to acquire other, more valuable, resources. As such, vigour is a resource that can be used to accomplish one’s goals and acquire further resources, which can help employees perform better in their jobs.

Similarly, self-verification strivers work to ensure that others do not form overly negative appraisals or overly positive appraisals of them. As a result of their efforts to self-verify, supervisors and peers better understand an employee’s true capabilities, habits, work styles, and limitations, and thus do not ask more from him or her than the employee is capable of accomplishing, leading to heightened DA fit. Increased DA fit, in turn, may result in greater job performance.

Although prior research has underscored the benefits of being perceived accurately by others, positive outcomes are not guaranteed (e.g., when norms are different) and it is also critical to examine the boundary conditions that determine when self-verification striving is most likely to yield positive outcomes. One possible condition is that of ethical climates (i.e., shared perceptions amongst team members that they practice and reinforce clear moral standards). For instance, in a work unit in which unethical culture prevails, peers fail to set an example of ethical business behaviour, make unethical decisions, and do not support each other to act ethically. As a result, one can never be sure whether information shared by others is true, leading peers not to accept or confirm self-verifying information and leading high self-verification strivers to exert additional effort as they repeatedly attempt to show their true selves. In addition, even when self-verifying information is accepted as true, peers working in an unethical environment may take advantage of professed weaknesses or will be unwilling to accommodate their peers’ strengths by adjusting their work arrangements, leading to lower DA fit. As such, ethical team culture may alter the relationships between self-verification striving and vigour and between self-verification striving and DA fit such that self-verification striving only positively relates to these outcomes when working in teams with a high ethical climate.

Study procedure and participants

In order to learn more about the effects of self-verification, vigour, DA fit and ethical climates on employee performance, we conducted a two-wave (two-month interval) and a multi-source (employees and their supervisors) survey to collect data from 222 employee-supervisor pairs at two organisations located in a city in southern China.

At time 1, we distributed questionnaires to employees in each organisation and asked them to assess their levels of self-verification striving, self-esteem, and demographic information as well as their work group’s ethical climate. Approximately two months later, we distributed time 2 survey to the employees who responded to the first survey and their supervisors. Employees were asked to assess vigour and DA fit while supervisors were asked to report their own demographic information and rate the subordinates’ job performance.

Results and discussion

Our study confirmed that people high in self-verification striving were in fact likely to be better performers as a result of their heightened vigour and increased DA fit. In addition, we found that ethical work climate significantly enhanced the relationship between self-verification striving and our intervening variables, as well as the indirect effects of self-verification striving on job performance via vigour and DA fit.

Our findings inform management practice in several ways. First, organisations that wish to enhance employees’ job performance and heighten employee vigour and DA fit levels may consider selecting for self-verification striving. Applicants high in self-verification striving should also avoid presenting idealised versions of themselves or suppressing their propensity to self-verify out of a fear of making a bad first impression. Although giving selection weight to self-verification striving is likely to help boost the performance of new employees, the question of how managers can motivate existing employees who happen to be low in self-verification striving remains. One idea might be to employ organisational policies that link employee identities with work tasks (e.g., letting employees choose self-reflective job titles).

Moreover, we found that self-verification striving was positively related to vigour and DA fit only when employees worked in a high (rather than low) team ethical climate, indicating that managers should strive to foster these climate perceptions. Simply providing employees with a written copy of ethical codes can foster such perceptions, as can linking compliance with ethical policies to formal rewards. At the same time, supervisors must go beyond setting an example of ethical behaviour to actively promoting and rewarding ethical behaviour. Thus, we suggest that in order to ensure that individuals high in self-verification striving are able to preserve their vigour, experience high DA fit, and reach their performance potential, top managers should take measures to foster strong ethical climates.

This is a condensed version of an article which originally appeared in Human Relations here. Emily M. David, Tae-Yeol Kim, and Jiing-Lih (Larry) Farh are members of the Organisational Behaviour and Human Resources Department at CEIBS. Xiaowan (Lucy) Lin is a member of the Faculty of Business Administration at the University of Macao. Fan Zhou is a member of the School of Management at Zhejiang University.