KOLs netting 800 million RMB overnight? An in-depth look at China’s influencer economy

By Lin Chen

China’s “Singles Day” e-commerce extravaganza got an early start this year. On October 20, the annual shopping frenzy was ignited by Li Jiaqi and Viya, two of China’s top livestreamers. In a livestream that ran until 2am the next morning, Li Jiaqi hawked products without a moment’s rest. Viya also gave her followers a treat in the form of blind box lottery. Figures showed that Li Jiaqi and Viya had 150 million and 130 million viewers respectively, with final gross merchandise value (GMV) of 3.3 billion RMB and 3.5 billion RMB. Industry insiders reckoned that the two netted 600-800 million RMB each in one night.

As livestreaming e-commerce finally steps into the spotlight, the influencer economy, despite its small scale, is gathering considerable momentum. At the same time, however, the influencer economy as a brand new business model is subject to uncertainties in terms of sustainability, performance evaluation and risk control. Is the influencer economy a lasting buzz or will it soon go bust? How can it pave the way for new retail business models to flourish?

How long does it take to become number one in an industry?

For Nestlé, the answer is 153 years. For, Coca-Cola, Haagen-Dazs and Givenchy, it was 134, 99 and 68 years, respectively. Today, however, these time-honoured brands are increasingly finding themselves challenged by direct-to-consumer (DTC) Chinese brands like Genki Forest, Saturn Bird Coffee, Chicecream and Florasis, which have achieved the top spot in their industries in just a short time by leveraging the power of social media and influencer marketing.

The head of Tmall reaffirmed this trend and predicted that with the domestic market as the mainstay, China should see a dramatic uptick in the number of DTC (or new consumer) brands in the next 5-10 years. He also predicted that, in the next three years, the Tmall marketplace will become home to 1,000 DTC brands with annual sales of over 100 million RMB each.

The DTC model alters the way products reach consumers by transforming sales and marketing practices, thereby disrupting the retail industry and changing the relationship between brands and consumers. DTC brands have three features: borrowed supply chains; a heavy dependence on online marketing; and a reliance on social media marketing and influencer marketing to reduce traditional channel and SKU costs. By virtue of a handful of top-selling products in vertical market segments, the influencer economy has boomed within a short timeframe.

How can we explain the flourishing of the influencer economy?

According to statistics, an annual total of $600 billion (USD) is spent on online marketing globally, with about $15 billion going to influencer marketing. Forbes reveals that DTC brands have outperformed their traditional counterparts during the coronavirus pandemic of 2020, forcing the latter to shift its investment focus toward influencer marketing.

Take for example the consumer market, which accounts for 10% of China’s GDP. In the past, although 23% of revenue was channelled into traditional marketing, a large amount of valuable consumption data was still lost due to ineffective ad placement and various intermediaries that obstructed direct interactions between brands and consumers. In stark comparison, influencer marketing and social media marketing makes better use of consumption data and connections with consumers to help address traditional businesses’ pain points regarding SKU and product orientation.

Change is not confined to the consumer sector. Hit by the COVID-19 outbreak, a growing number of funds, insurance and healthcare companies, and other B2B companies have set their sights on influencer marketing.

Given its halo effect and prodigious money-making opportunities, young people now perceive “influencer” as one of the most sought-after jobs. According to a survey conducted by Xinhua News Agency three years ago, “livestreamer” and “influencer” were top two career choices for the post-1995s. For teenagers in the UK and the US, “influencer” has surpassed “astronaut” or “scientist” to reach number one on the list of occupational dreams.

Why do so many people want to be influencers? And, how lucrative can the job be?

Li Jiaqi and Viya can earn 100 million RMB in a year. At the same time, Kylie Jenner, the highest-earning American internet celebrity, was paid a staggering $1.2 million for every single post on her social media channels.

Surprisingly, statistics show that livestreamers do not have to be big-name marketers like Kylie Jenner to reap profits. For instance, a nano-influencer with less than 1,000 followers should have no difficulty making dozens of dollars from a post, whilst a mega-influencer boasting 1 million fans may pocket around $4,000 in exchange for releasing a video.

While the influencer economy is heating up, some believe it will go downhill sooner or later. As a recent article in Harvard Business Review explains, though DTC brands have increased their customer traffic via influencer marketing, they will inevitably be beset by problems pertaining to scaling up, management and platform operations once their initial craze fades.

What roles can influencers play in the consumer decision-making process?

There are different levels of consumer involvement in purchase decision-making. This can be exemplified by the low degree of involvement when thirsty consumers buy bottled water versus the high degree of involvement when purchasing valuable items.

Theories in economics, and behavioural and social sciences suggest that product purchases featuring low degrees of consumer involvement are more likely to be influenced by external factors such as public opinion. Such “irrational factors” may sow the seeds that quickly grow into purchasing items. By contrast, purchase decisions that require a high level of consumer involvement will go through more complicated information processing.

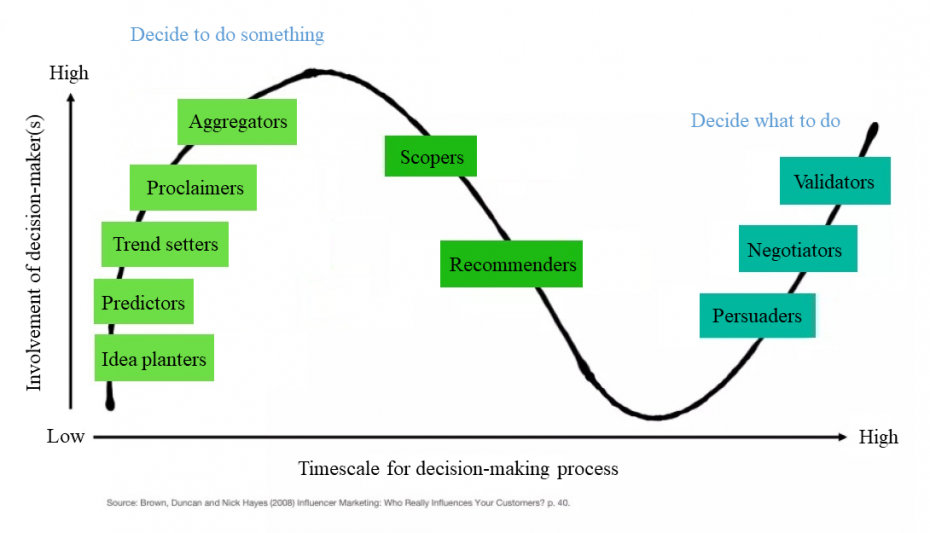

Looking at the graph above, if the vertical axis represents “involvement of decision-makers” and the horizontal axis represents “timescale for a decision-making process”, we can infer that influencer roles are more likely to be found on the left half of the curve (i.e. closer to “idea planters”).

According to Viya, “products suitable for livestreaming e-commerce” are those in the 30-50 RMB price band, as they generate low-involvement purchase decisions. Consumers may already be thinking about making a purchase before watching livestream shows; some may already know their personal needs, but still wait for influencers to provide comparative analysis before coming up with a viable plan; and others may be looking for validation to prove that their purchase decisions are low risk. As part of this life-cycle, different types of influencers are able to meet the demands of consumers in different phases of decision-making.

It is a misconception that those who have the loudest voices are the most powerful; and those who have larger fan bases exert greater influence over consumer purchasing decisions. In fact, KOLs cannot be evaluated merely by their fan base or level of interaction. Instead, a multi-dimensional evaluation system should be put in place. In practice, in addition to common input-output tools, the modelling of user, influencer and target audience personas for comparative overlap analysis can produce indicators on which influencer marketing effectiveness in different sectors or product categories can be evaluated. In this way, products can be better matched to consumer purchasing decisions.

What is the relationship between influencers, brands and consumers?

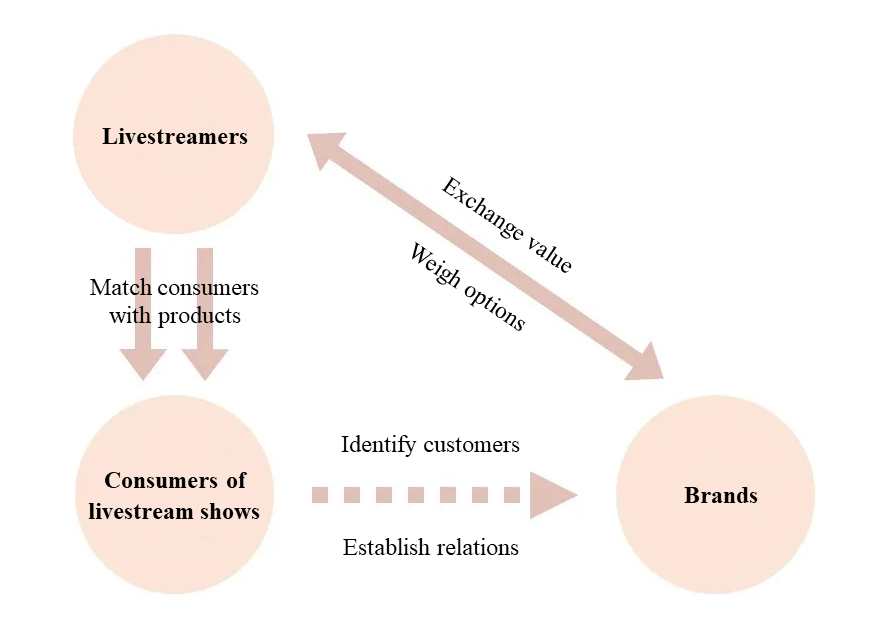

So, what do influencers want? Fame and fortune. On one hand, livestreamers always need to attract more followers to increase their fame; hence, they promote the idea that “my livestream shows offer more favourable prices”. On the other hand, brand sponsors’ generous offers enable them to reap a fortune. What do fans expect of livestreamers? The answer is always the same: “diverse offerings, fast delivery, good quality and money-saving purchases”. What do brand sponsors expect of livestreamers? For one thing, to boost sales. For another, they expect them to single out potential customers (i.e. a target audience amongst the livestreamers’ fan base). Furthermore, they expect them to direct traffic to flagship stores so as to generate repeated purchases. That is why brand sponsors are willing to accept the high prices demanded by livestreamers and sustain losses.

In general, the relationship between livestreamers and brands is characterized by their exchange of value and weighing of options.

How do influencers prevent fans from being lured to competitors or platforms run by the brands themselves?

The key lies in offering the most favourable price, as this practice simplifies the decision-making process for followers, makes them happy to cherry-pick products alongside livestreamers and become even more loyal.

Brands are looking for the right livestreamers for their products. To examine the overlap between the livestreamers’ fans and brands’ target audiences, brand owners must take repeated chances on a large number of livestreamers. Through such costly trial and error, they may find livestreamers who are compatible with their brand values and who are able to deliver high loyal customer conversion rates. All in all, their deal is by no means one-off – there is a long-term, dynamic matching mechanism.

The pursuit of “diverse offerings, fast delivery, good quality, money-saving purchases” is manifested throughout the influencer marketing process. For example, to ensure “fast delivery”, Taobao and Tmall livestream shows make possible “citywide delivery in an hour”; to ensure “good quality”, livestreaming e-commerce abandons the price war approach and embraces brand upgrading; to enable diverse offerings and help save money, livestream shows usually offer low prices, and introduce tie-in sales. Of course, these four consumer demands can hardly be satisfied at the same time. So, they must persuade target audiences to set their own priorities.

What are the risks of influencer marketing?

As a new business model, the influencer economy redefines the underlying structure that connects the production, distribution and monetization of content, thereby reshuffling the whole retail landscape. As the saying goes, “while water keeps a boat afloat, it can also capsize a boat” – the influencer economy has its hidden perils and pitfalls.

First and foremost among the perils is reputational risk. Influencers somewhat resemble celebrities and their private lives or inappropriate comments could expose brand owners to substantial reputational risk. As is often the case, livestream viewers are not loyal customers of brands, therefore, brand sponsors need to strike a proper balance between attracting usually disloyal new shoppers and retaining loyal long-term customers. For luxury brands, it is particularly worth noting that favourable prices available in livestream shows may “badly hurt” some loyal customers, who think heavy discounts tarnish the brands’ high-end positioning.

Second, economic risk. According to a global survey, two thirds of advertisers have encountered misleading marketing, click farms, paid fans and overstated GMV or influence. Influencer marketing during the coronavirus pandemic could be a short-lived success, as it might be attributed to temporary changes in consumers’ behavioural habits. If brand owners are in a feverish state, a chain of fraudulent activities will be here to stay, which may even lead to legal risk. Around the globe, countries are working on relevant laws and doing regulatory work.

For example, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC)’s 2016 Endorsement Guides went into detail about how influencers can stay on the right side of the law, for example, by using hashtags such as #ad, #sp and #sponsored to alert consumers to sponsored content. Buying fake comments has also been considered a criminal violation in the US since last year.

Currently, shoppers still have mixed feelings about influencer marketing. In a study conducted for the BBC, only about 4% of British said influencers are trustworthy, around a third mistrust influencers and approximately two thirds believe followers are nothing more than the cat’s paw for influencers. Against this backdrop, if the influencer economy is to continue to thrive, influencers should not only focus on earning fame and fortune, but also try to promote a wider variety of products via livestreaming, exert greater influencer over consumer decision-making, and create more value for brand sponsors, consumers, the industry’s value chain and society.

Lin Chen is an Assistant Professor of Marketing at CEIBS. For more on her teaching and research interests, please visit her faculty profile here.