Contextualising the Sharing Economy

By Guo Bai and Rama Velamuri

The sharing economy (SE) continues to mobilise dispersed and underutilised private assets for collective usage on a scale previously unimaginable. From home sharing (e.g. Airbnb, Couchsurfing) to car sharing (e.g. Uber, Didi), sharing professional expertise (e.g. Upwork, Taskrabbit), parking and storage space sharing (e.g. Justpark, Neighbor) and childcare sharing (e.g. SitterCity), the different activity categories of the SE demonstrate sizeable variation in structure and scalability.

In all contexts, however, the SE is a complex structure composed of multiple actors (asset owners, asset users and sharing economy platforms) and multiple sets of relationships. As such, the SE represents a unique governance structure, one that can be characterised as a set of coordinative mechanisms that engage participants in a collaborative process, resolve conflicts, and yield certain collective performance.

So, in which contexts is the SE most likely to serve as an effective governance structure when compared with other types of governance structures?

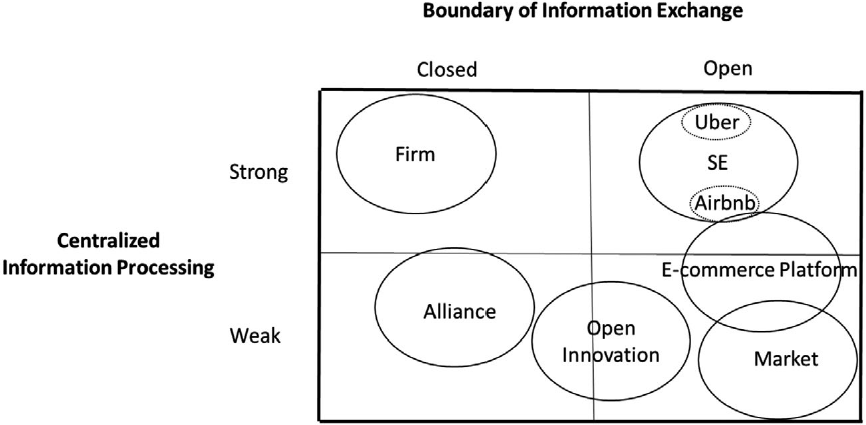

Figure 1: A comparison of organisational forms from the perspective of information communication and processing

For one, different organisational forms differ with respect to their boundary of information exchange and their reliance on centralised information processing (see Figure 1).

In the case of the SE, the rapid development and integration of information and communications technologies has allowed participants to create wholly new organisational forms and collaboration activities. Critical to this is the fact that sharing economy platforms (SEPs) exhibit markedly open systems with wide information exchange amongst their participants, but at the same time possess strong centralised coordinative mechanisms for information processing.

Specifically, open and flexible boundaries allow SEs to invite wide participation from private asset owners and enable market-like peer-to-peer transactions; at the same time, centralized information processing plays a key role in solving problems regarding effective data handling and user trust.

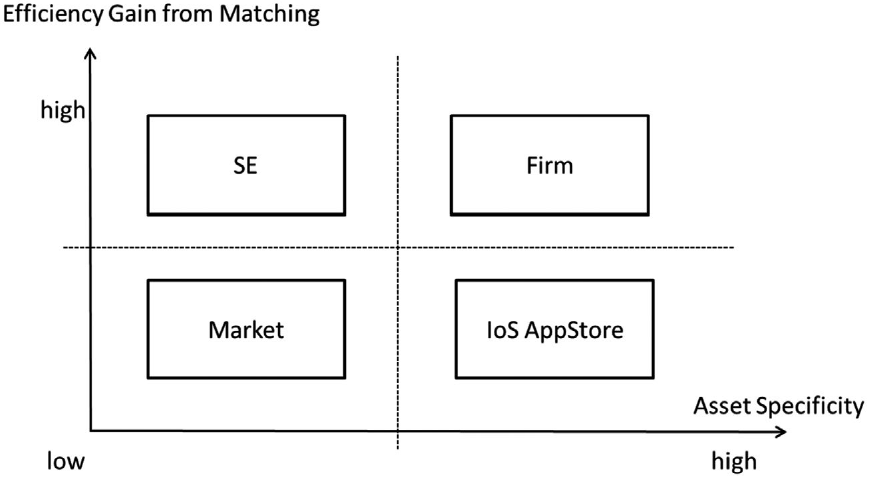

Figure 2: Contextualising the SE through transaction characteristics

The SE can also be contextualised through differing transaction characteristics (see Figure 2).

In particular, the greater the reliance on matching efficiency (in matching asset users with asset owners) and the lower the asset specificity (i.e. the degree to which a thing of value can be readily adapted for other purposes), the more likely the transaction will be organised in an SE governance structure.

This is due to the introduction of increasingly sophisticated algorithms for searching and matching, efficient recommendation systems and the leveraging of location-based technologies. Moreover, successful SEPs are those which provide ever-improving means of increasing matching efficiency, while also systemically decreasing transaction costs.

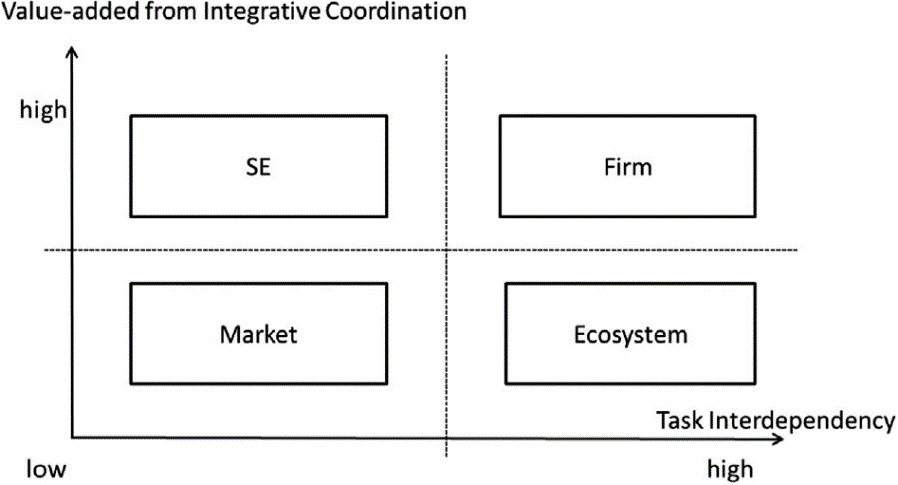

Figure 3: Contextualising the SE through task characteristics

Finally, it is also possible to contextualise the SE through task characteristics (see Figure 3).

In general, the greater the system level value-adding potential of central coordination and the lower the interdependence between subsystem level tasks, the more likely is it that tasks will be performed under an SE governance structure.

Furthermore, SEP-provided algorithms and processing capabilities can be especially effective in orchestrating large-scale collaborative activities when the interdependence amongst the tasks carried out by asset owners is low.

Managerial and organisational implications

The above findings offer valuable insights and implications for SEPs.

Firstly, the strongest value creation mechanisms in the SE rely on the centralised role of SEPs to broker transactions and to coordinate collaborations. To succeed in the SE, SEPs must leverage emerging technologies (particularly location-based technologies and data capture and analysis tools) to become better intermediaries. This will encourage easier collaboration amongst all participants as well as wider participation on a larger scale.

Our analysis is also relevant to a larger wave of organisational research on new organisational forms made possible by the advance of digital technologies. The leveraging of cheaper and stronger information processing by SEPs, for example, demonstrates the capacity for greater integrative coordination both within and beyond organisational boundaries.

Ultimately, understanding the SE’s evolution is critical to grasping the potential for collaborative bodies extending beyond a single firm that can act more like ‘organisations of organisations.’

This article refers to the study entitled, “Contextualising the Sharing Economy,” published in the Journal of Management Studies here.

Guo Bai is an Assistant Professor of Strategy at CEIBS. For more on her teaching and research interests, please visit her faculty profile here.