Incremental vs Radical Innovation: A Case Study of Germany and the US, with Insights for Managers in China

Richard Carney

Assistant Professor of Strategy

CEIBS

CEIBS Professor Richard Carney is from Canada and has lived in eight countries across four continents. He is the author of the multiple award-winning book Authoritarian Capitalism, with which he became the first scholar from a business school to win the Masayoshi Ohira Memorial Book Prize since its inception in 1985.

Click the image to view the recording of the webinar online.

Every year, CEIBS conducts a survey asking managers of hundreds of firms in China what their greatest internal challenges are. Every year for the past six years, the number 1 and 2 challenges respectively are finding and retaining talent, and innovation capability. Typically, the type of talent most difficult to find is related to innovation, so these top two challenges are strongly related.

So how do companies based in China address this problem? One of their main go-to solutions is to look overseas and buy companies with the appropriate innovation capabilities. However, to ‘win’ the high-tech race, to successfully keep innovating, Chinese firms need to ensure that they fully understand the type of innovation that they want to pursue, and the type that best fits their circumstances.

The two ‘innovation types’ I’m talking about are ‘incremental’ and ‘radical’. We think of a radical or disruptive type of innovation when a new product or service comes along and makes previous ones obsolete. The introduction of the smartphone is a useful modern example, but the transition from horse and buggy to automobile is perhaps more illustrative of what truly radical innovation looks like. Contrastingly, the ‘incremental’ innovation type describes small improvements in subsequent models that come after the introduction of that first radical, ‘game-changing’ product or service.

Some global economies, like the US, are better at encouraging and sustaining radical innovation, whereas some, like Germany, are better at incremental innovation. The key question is why? What makes these economies so consistently good at supporting these different innovation types? By understanding both cases, we can take this knowledge and apply it to China.

Incremental vs Radical – Market Institutions are Key

Think about how an entrepreneurial company goes about deciding how best to bring their innovative idea to the marketplace. Undoubtedly, their strategy will depend on the structure of the market institutions of the economy in which they are located. Let’s take a brief look at the inherent differences in market institutions between Germany – a prime example of a Coordinated Market Economy (CME) – and the US, a Liberal Market Economy (LME).

The five key market institutions needed for comparison are:

1 Corporate Ownership

2 Employee Relations

3 Financial system

4 Education and Training

5 Inter-company relations

For the purposes of this article, we’ll be focusing on the first two: corporate ownership and employee relations.

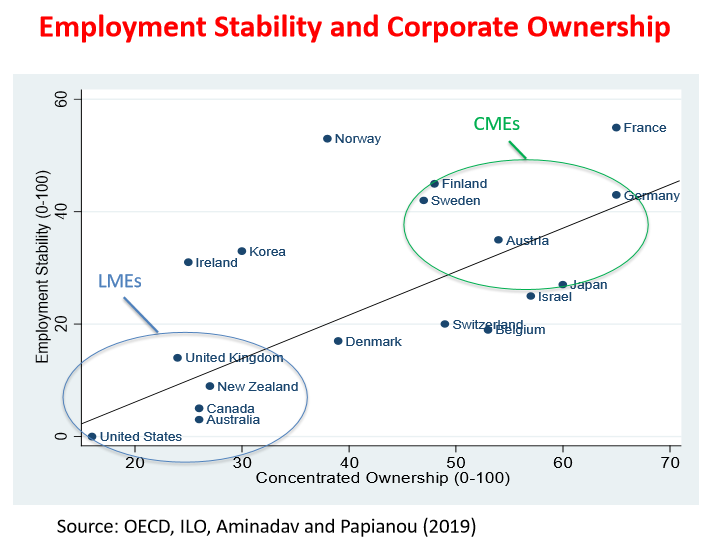

In Germany and similar EU economies, corporate ownership largely rests with powerful business families, the government, and other large actors such as banks and labour unions. The consequence of such concentrated blocks of ownership is that company CEOs are monitored closely by company owners. Company owners want their CEO to focus on the long-term future, because they usually want to build something that endures.

In the US, large companies are much more diffusely owned; hundreds if not thousands of small shareholders all hold interests. Managers must provide updates on the firm’s performance every quarter to show that they aren’t going against the shareholders’ wishes. This produces a stronger focus on short-term results. Consequently, managers have more decision-making power, and experience less monitoring. Additionally, they experience greater autonomy but also more regular short-term accountability.

In terms of employee relations, German labour unions are strong, allowing workers to bargain with management. Workers have a voice on layoffs and working conditions. Wages are set through negotiation and are largely consistent across a given industry. Poaching generally does not occur. Consequently, employment for the average worker in Germany is stable and long-term employment is fairly common.

In the US, unions are comparatively weak, wages are set by the market, and workers have little influence on conditions. This leads to more unstable employment, and short-term employment is more common. The latest ILO and OECD figures show the unionisation rate for Germany is 26% vs 10% for the US. Germany’s average job tenure is 11 years, vs 4 for the US.

The key point here is that corporate ownership and employee relations conditions in Germany both encourage a focus on the long-term. There is a long-term emphasis on coordination and collaboration between capital, labour and firms. In the US, more of a short-term focus and relations exist between these three entities, because it is so much easier to hire and fire employees, and the more numerous shareholders generally do not share common goals except the need for regular quarterly gains.

Again, the innovation implication of all this is that Germany encourages more incremental innovation and the US (exemplified by Silicon Valley) more radical. Germany’s workers are secure in their jobs, happy to invest in highly specialised training and skills development and far less likely to be lured away to other firms. German firm owners take a long-term view and build for the future. By contrast, US firms can easily find and attract employees with the skills they need, and easily find venture capital to invest in their ideas. US firms’ diverse shareholding owners focus on quick gains, motivated by stock price.

This is reflected in the best-known companies in both cases. For Germany and similar CMEs, companies are well established and compete on quality, such as Mercedes Benz, Bosch or Siemens. In the US and similar LMEs, the best-known companies are ones competing on novel technologies and ideas, like Uber, SpaceX and Google.

Where’s China in all of this?

While we must be wary of judging China as a monolithic economy – because it isn’t – we can draw some confident conclusions when it comes to the type of innovations that its market institutions encourage. Averaging out conditions across this large and varied economy, China has very high concentrated ownership and high employment stability. This makes it much more like Germany than the US, innovation-wise. Technically, China is more like Germany than Germany itself in terms of displaying the incentives needed to create incremental innovations!

A useful indicator of China’s current innovation status is to look at growth over time. Between 2015-2016, China was number 6 in the top 50 nations for the number of patent applications to the EPO (European Patent Office). By 2019, China was number 4 on this list, increasing its application rate by almost 30% compared to the previous year. For an emerging economy with various market institutions yet to reach full maturity, China is performing extremely well on patent application rates.

Unlocking Germany’s Innovation Secret

If China is more like Germany than Germany itself in having the right conditions to encourage incremental innovation, how can Chinese firms innovate as successfully as German ones? If you want to innovate like the Germans, you first have to understand how Germany’s innovation ecosystem works in practice. Germany has a big ‘open secret’ in its innovation model – The Fraunhofer Institute.

When entrepreneurs want to bring their idea to market, they need to convince investors of the viability of idea and its market potential. This is called bridging the investor gap, or crossing the ‘Cash Valley of Death’! In Germany, many companies bridge this gap so effectively due to the Fraunhofer Institute. It is the largest applied research institute in Europe. It has 74 institutes and research facilities, almost 30,000 staff and an annual budget of over 2.8 billion euros. Companies begin with basic or strategic research on an idea or innovation and then ask Fraunhofer to participate. Fraunhofer not only lends its vast technical expertise and resources, it also leverages its substantial reputation to convince a bank to finance the innovation’s development and commercial expansion.

The Fraunhofer Institute sits right in the middle of the German economy’s model of incremental innovation that is built on collaboration and coordination between different entities. It not only exemplifies the benefits of this model, it also magnifies them.

Understanding the US Innovation Funding Context

The US’s innovation funding context is very different to Germany’s. Early-stage development funding comes mainly from the US Government, companies or angel investors. US Government departments have been intimately involved in major global innovations; the smartphone came about through developments originally funded by the DoD (Department of Defense) and even the Internet itself was a DARPA creation.

Once an innovation is formed in the US, venture capital financing is needed to lift it off the ground. The much more liquid markets of venture capital financing, rather than bank financing, represent a key factor in the US’s propensity for fast-paced, radical innovation. Like Germany, US market institutions directly encourage one type of innovation over another.

Can you Have Your Innovation Cake and Eat it too?

While Germany and the US have shown that they excel at incremental and radical innovation respectively, the good news is that these systems can complement one another. A useful example is the global automotive industry. Consider the many recent radical innovations in electric and autonomous vehicles that are developed in the US and were then subjected to continuous, incremental innovations and improvements in Germany. This is just one of innumerable examples of how innovation ecosystems can be combined by companies who truly understand and appreciate their worth.

While China’s innovation ecosystem strongly incentivises incremental innovation over radical innovation, mergers and acquisitions allow for managers to secure access to both innovation types successfully. Provided you can build up a comprehensive understanding of the innovation ecosystem in which your target acquisition is located, you can enhance your competitive advantage in terms of your innovation strategy by:

01 Improving your analysis of whether a new innovation-related acquisition will add value and how best to conduct the merger to ensure successful collaboration.

02 Helping you identify the type of innovation your firm should pursue by working with, rather than against, the innovation incentives generated by the institutional ecosystem in which your firm is located.

These are crucial considerations for any manager in any company operating in China, whether it is Chinese-owned or a foreign-held interest. Since the overall pace of global innovation will only continue to accelerate, a realistic and effective innovation strategy will become increasingly essential as China’s market institutions rapidly mature.

Please click WeChat link to read on the phone.