Will China’s Economy Maintain Its Medium-to-High-Speed Growth in the Next Decade?

By Zhu Tian

The path taken by economic growth is never straight and economists are deeply divided on the causes that have led to China’s recent economic downturn. Is it cyclical, structural, or due to something else?

I. Main Reasons behind China’s Economic Downturn in Recent Years

Cyclical fluctuations in the growth rate of any economy appear to be inevitable, and China is no exception. Although its economy grew on average 8.48% per year for more than four decades, it actually went through four peak and trough cycles. After 2015, however, the growth rate hovered around 6-7%, significantly lower than the average of 10% of the previous 10 years, bucking the trend in cyclical behaviour.

Some economists have laid the blame for this economic slowdown at the door of so-called structural factors, such as lagging institutional reforms, a shrinking demographic dividend, and lack of innovation. However, given that nothing has changed dramatically in China’s economic structure over these last few years, it is hard to use these factors to explain this recent economic decline. First, the impact of China’s demographic dividend in its economic growth has been exaggerated as changes in demographics generally affect economic growth gradually over the long-term. As for innovation, a range of indicators reveal that China’s level of innovation is actually rising rapidly.

Even though the slump in China’s economy can be explained in part through some structural factors on the supply side, sharp deceleration should be analysed from the point of view of demand-side factors (i.e. investments, consumption and exports).

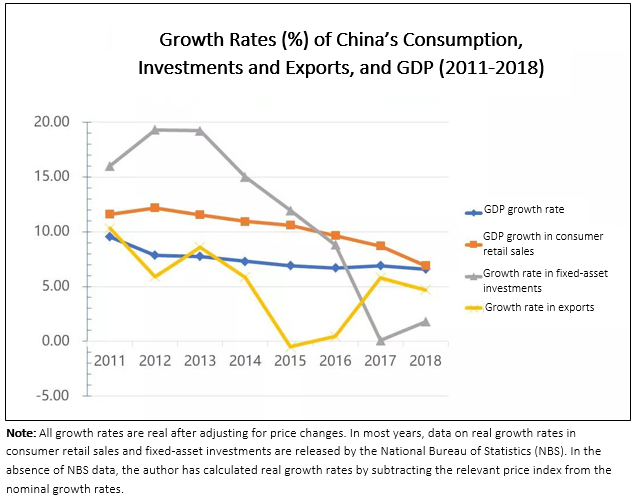

As the growth of China’s investments, exports and consumption declined significantly between 2013 and 2018, so did its GDP growth rate. The figure below clearly shows that China’s economic deterioration over the past five years was triggered primarily by the nosedive in fixed-asset investment growth.

Compared with investments, export growth plunged between 2015 and 2016, while the growth in imports required to produce exports also declined. As a result, net exports as part of aggregate demand did not change much. It can also be seen from the figure that up until 2018, consumption grew faster than GDP during the downturn, and as a result, the share of consumption growth in short-term GDP growth increased. This phenomenon is often viewed as an improvement in the quality of economic growth. In this case, however, it was the natural consequence of a steeper decline in investment growth than in GDP growth, and was thus unrelated to any quality in growth.

So, what triggered such a massive decline in China’s fixed-asset investment growth?

First, after 2013, government policy goals became more diversified. Instead of simply pursuing higher GDP growth as it had done before, the Chinese government turned its attention to environmental protection and fighting government corruption, which cooled the investment scene, naturally putting a brake on China’s economic surge as the investment boom levelled off.

Second, fiscal and monetary policies became more contractionary than expansionary, perhaps as a defensive reaction to a flurry of criticism levelled at the strong stimulus policies rolled out in 2009. Looking at the graph again, it is clear that investment and export growth slid dramatically between 2014 and 2015. At that time, the Chinese government should have adopted counter-cyclical economic policies (i.e. proactive fiscal and monetary policies, to stimulate economic growth). Instead, in 2016, it launched a pro-cyclical (tightening) macro-control policy to reduce overcapacity and encourage deleveraging. In 2016 and 2017, growth in both fiscal expenditure and money supply fell sharply. A tighter fiscal policy, especially a tighter monetary policy, was going to do nothing to reverse the pressure towards an economic downturn.

In my view, China’s economic tumble in recent years was not just the consequence of cyclical fluctuations, or the result of some vaguely defined structural factors, but rather the product of policy choices.

II. Misconceptions about China’s Economy

Why did the Chinese government adopt a so-called “pro-cyclical” tightening policy in the midst of a significant economic downturn? I think that it was because many economists and think-tanks, who held sway over government policy and public opinion, had some fundamental misconceptions about the Chinese economy. Specifically, the importance of investment in economic growth was underestimated, while the extent of loose money supply and high corporate leverage was overestimated.

As investment rates were significantly higher in China than in other countries, many economists believed that China had been relying too much on investment to –drive economic growth, which not only generated overcapacity, but also a high leverage ratio in the corporate sector. Based on this premise, China’s economic downturn could be blamed on excess aggregate supply, rather than insufficient aggregate demand, hence the need to cut overcapacity and deleverage.

In reality however, overcapacity at the macroeconomic level may not be the cause, but rather a consequence of an economic downturn. As an economy loses momentum, industries naturally suffer from overcapacity; inversely, as an economy picks up, recovery in demand naturally absorbs the overcapacity, sometimes even creating a shortage in capacity. If, rather than letting market mechanisms reset the balance, a government implements wide and sweeping one-size-fits-all measures to cut overcapacity, the risk becomes that this type of approach will actually exacerbate the slowdown.

Another misconception was that there was an excess in China’s money supply, as reflected in the high M2/GDP ratio, which had created asset bubbles, especially in the real estate sector, and increased leverage in the corporate sector, leading to high financial risks.

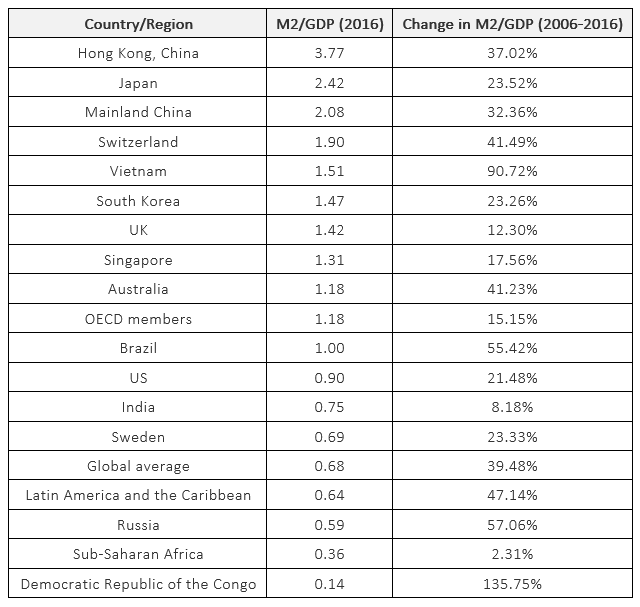

According to the data in the table below, China’s M2/GDP ratio hit 2.08 in 2016, amongst the highest in the world, more than twice that of the US, and three times the global average. In this sense, China’s M2/GDP ratio seemed to be too high. Nevertheless, there are no economic theories indicating that a high M2/GDP ratio is bad for an economy. In fact, such ratios are lower in low-income African countries, but higher in high-income OECD countries.

Global Comparison of the M2/GDP Ratio and Change:

Generally speaking, market economies decide whether to relax or tighten their monetary policy based mainly on inflation and unemployment rates. Unless inflation is too high, it is hard to claim that there is too much money supply in the economy.The M2/GDP ratio varies considerably across the world, but it bears no clear relations to economic growth, inflation, asset price bubbles, or to the risk of financial crises. For example, this ratio was never high in the US, and was stable at 0.72 even in the years 2001-2005 leading up to the subprime crisis in 2006. Notwithstanding, huge bubbles still emerged in its housing market, eventually sparking a global financial crisis.

Furthermore, the relatively high M2/GDP ratio in China should be no surprise, since M2 is largely synonymous with bank deposits. Given China’s high savings rate and lack of opportunities to channel this money into other financial assets, bank deposits have become the primary savings vehicle, giving rise to a high M2/GDP ratio. More deposits mean more bank loans, which constitute debt taken on by borrowing enterprises. Under such circumstances, it follows that the ratio of corporate debt to GDP will rise. This chain of events is the natural consequence of high savings rates, and does not constitute per se the basis for financial risk.

Some economists would agree that we may explain China’s higher M2/GDP and macro leverage ratios in this way, but argue that it is the relatively fast surge in these ratios that is hazardous. Nevertheless, the table above illustrates that rising M2/GDP ratios between 2006 and 2016 was a global phenomenon and not unique to China. In fact, China’s M2/GDP growth rate was below the global average (39.48%), while even the US was experiencing a surge of 21.48%. The past decade has seen money supplies growing rapidly around the world, in stark contrast to slower GDP growth, lower inflation rates, and lower interest rates. This is a new macroeconomic phenomenon that is still little understood. Moreover, the rise in macro leverage ratios amongst Chinese enterprises reflected, on closer examination, growing liabilities amongst local governments’ financing platform companies, and not over-leveraging in ordinary enterprises, and even less so amongst private enterprises.

III. Three Engines for Mid-to-long-term Economic Growth

To understand the mid-to-long-term prospects for China’s economy, we need to first distinguish economic fluctuation from economic growth. In economics, economic growth generally refers to the sustained increase in a country’s capacity to produce goods and services over a mid-to-long-term period, while economic fluctuation refers to the short-term ups and downs in GDP growth rates along a long-term growth trend.

By definition, economic growth is about increasing production and supply, not about demand. Consequently, the three drivers of long-term economic growth are physical capital accumulation (investment), human capital accumulation (education), and technological progress, and not the three factors often cited in the media of consumption, investments and exports. The latter are three demand-side factors that affect short-term economic fluctuations. The only common element between the two sets of factors is investments, because they generate both short-term demand and long-term supply.

With regards to the first engine of economic growth, China’s investment rate, which has been among the highest in the world for around three or four decades, is underpinned by China’s high savings rates, and is therefore a major driver of China’s rapid growth.

For the second engine of growth, research by two economists, Eric Hanushek of Stanford University in the US and Ludger Woessmann of LMU in Munich, Germany, reveals that the quality of basic education is the best predictor of a country’s economic growth. According to their data, the quality of China’s basic education now matches the levels achieved in developed countries, forging solid foundations for economic growth.

Finally, the impact that education has on economic growth in developing countries is primarily from people being able to capitalise on advanced technologies learnt from developed countries. A number of indicators show that the pace of technological progress in China is the fastest in the world, providing the third engine powering China’s economic growth.

If we look at China’s economy in the same way we would analyse the fundamentals of a listed company, then China would score very well on the three counts of investment, quality of education and speed of technological progress that have underpinned China’s rapid growth over the past four decades. A large part of China’s strength on all three fundamentals can be attributed to the central values that characterise the Confucian culture, which are the importance attached to education and thrift.

The institutional changes brought about by China’s reform and opening-up policy were a prerequisite for China’s economy to take off. Nevertheless, the distinctive catalyst for the economic miracle that changed the face of China and other East Asian economies was the Confucian culture of education and thrift.

The fact that cultural advantage is not something that can disappear in the space of a generation or two, gives us grounds to be optimistic about the prospects for China’s economy. So long as China pursues its course to becoming a more market-oriented economy and continues to implement policies that enshrine reform and opening-up in the rule of law, we have reason to believe that China is set to join the ranks of developed high-income countries in the foreseeable future.

IV. China’s Economic Outlook against a Background of Trade Friction

The frictions that have marred trade between China and the US for nearly two years now are inevitably going to dent demand for Chinese exports. However, given that exports to the US only make up less than 4% of China’s GDP, even if the US imposed a 25% tariff on all exports from China to the US, the short-term impact on China’s GDP growth would still be limited. Looking at the longer term, trade friction may trigger a technology war. While such tension could hamper China’s technological progress, it could also be the catalyst for home-grown innovation.

Economic and political tension between China and the US may become the new normal over the next 10-20 years: over the longer term, this friction could shroud the economic outlook for China and the rest of the world in uncertainty, and undermine market and corporate confidence in the future.

While external trade frictions may slow down the rapid rise of China’s economy, but cannot reverse it. The real engine that will determine its longer term economic progress in the future lies within China itself.

In the short term, therefore, China needs to loosen up those fiscal and monetary policies that have been overly contractionary in recent years. In the longer term, China will be able to depend on its three robust fundamental drivers, namely investment, quality education, and rapid technological progress, to achieve medium to long-term economic growth. So long as China keeps its course towards a more market-led and rule-based economic system, its economy will be able to achieve a medium-to-high-speed growth of 6%-8% over the next decade.

Zhu Tian is the Santander Chair in Economics and an Associate Dean at CEIBS. For more on his research and teaching interests, please visit his CEIBS faculty profile here.