If exports shrink, what will drive China’s growth?

By Zhu Tian

What does China’s ‘dual circulation’ strategy say about where its economy is heading? And, what will be the main driving force of China’s economic growth amidst the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and a rapidly changing international outlook? While further tapping international markets, China will largely anchor its future economic growth in the domestic market. By putting priority not on stimulating consumption, but on boosting investors’ confidence and sense of security, China may continue to maintain relatively rapid economic growth.

The Chinese market itself is big enough

Both the domestic and foreign markets matter for the Chinese economy. Nevertheless, the contribution of domestic market has been rising over the past decade.

By contrast, China’s exports as a percentage of its GDP (which previously ran above 30%) began to decline after the 2008 global financial crisis, have now fallen below 20% and will continue to trend downward in the future.

For one, China has grown much faster than the rest of the world. As the size of its economy grows bigger, China’s export growth (or the growth of overseas demand) will inevitably lag behind that of the overall economy, resulting in a shrinking share of exports as part of the GDP.

As the world’s second largest economy, China’s reliance on foreign markets is naturally lower than smaller economies such as Singapore, Switzerland and South Korea. US exports only account for 12% of its GDP, while Japan’s exports-to-GDP ratio is also lower than that of China. Even during the country’s economic heyday in 1990, Japan’s export ratio stood at as low as 10%. . As China’s economy develops further and becomes more mature, its reliance on exports will continue to decline. In the short run, turmoil in the global market and a gloomy world economic outlook are bound to negatively impact China’s exports.

This, however, doesn’t herald a growth bottleneck for most companies in China since the Chinese market itself is big enough. The population of Europe and North America combined is about 1 billion people. Before China’s reform and opening-up, Western European and American markets collectively represented a population of merely 650 million (less than 800 million even with the addition of Japan). Nevertheless, these economies managed to prosper by acting as each other’s trade and investment partners, without forging any significant trade ties with the former Soviet Union, Eastern Europe or most developing countries.

All this doesn’t mean China can close its door to other economies. This year, the Chinese government has repeatedly reaffirmed its commitment to establishing a ‘dual circulation’ development pattern, in which domestic and foreign markets can boost each other, with the domestic market as the mainstay. The pronouncement of this policy demonstrates that China will give full play to its domestic market while continuing to open up to the outside world.

Drivers of China’s growth

What then are the key driving forces underpinning China’s rapid economic growth in the past few decades? To what extent has international trade contributed to this growth? And, what will be the drivers of China’s future growth? Let’s start with a close look at the relationship between trade and economic growth.

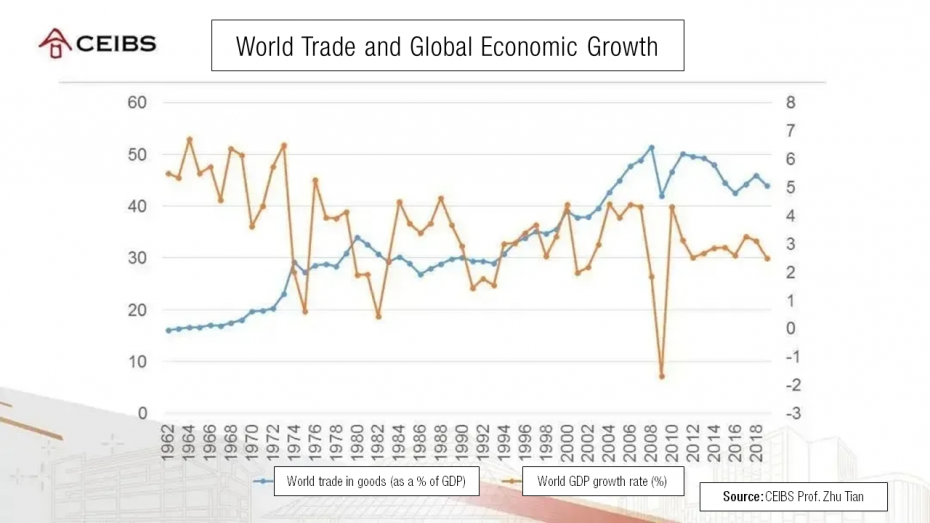

As indicated in the graph above, in the past nearly 60 years, echoing the rise of globalisation, the world’s merchandise trade-to-GDP ratio has shown a general upward trend, climbing from less than 20% to roughly 50%. However, this uptrend stalled after the 2008 global financial crisis. Over the same period, global economic growth has fluctuated greatly and generally trended downward.

This is not to say that increased trade has led to decelerated economic growth, but we can at least see that trade itself does not determine economic growth. It is certainly not why China has grown so much faster than other economies. After all, most economies have participated in the globalization of trade.

So, if trade and globalisation haven’t played the decisive role, what are the real driving forces behind China’s growth?

There are three engines of economic growth – namely investment, education and technological progress. These are different from the popularly known troika of consumption, investment, and exports, which are three demand factors affecting short-term economic fluctuations.

We shouldn’t confuse long-term economic growth and short-term economic fluctuations. In economics, ‘economic growth’ is normally defined as a sustained rise in productivity. A country is poor not because its people are reluctant to consumer, but because it suffers from a generally low level of productivity. Only investment, education and technological progress will bring about increased productivity. In the long term, a country’s consumption and exports are determined by its ability to produce competitive products.

It is not surprising that China has grown faster than developed countries. This can be attributed to the catch-up effect or ‘latecomer advantage’ that results from a low starting point. Obviously, this advantage is shared by all developing countries. Compared with other developing countries, however, China has some unique cards up its sleeve – namely, savings and education – which financially and intellectually enables China to learn and absorb Western technologies. In addition to human capital, investment is also essential for the adoption of advanced technologies.

In short, China’s economic growth over the past 40 years has been driven by investment, education and technological progress, and ultimately by its sky-high savings rate and high-quality basic education, both of which will continue to play a significant role in the future. So, how fast will the Chinese economy grow in the next 10-20 years? My answer is about 6% a year, most probably.

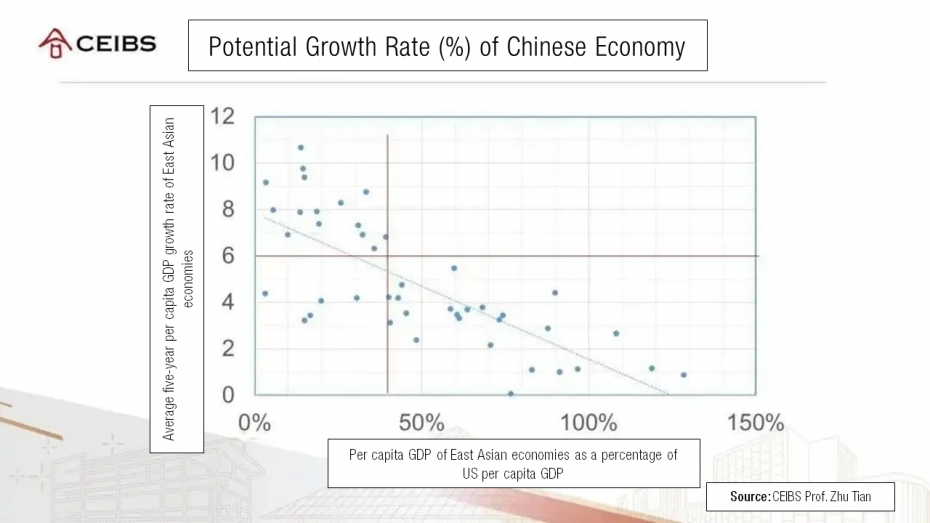

The graph above shows the development trajectories of several other East Asian economies, with each dot representing the growth rate of an East Asian economy at a given stage of development.

The horizontal axis shows their per capita GDP as a percentage of the US per capita GDP and the vertical axis measures their per capita GDP growth rates. The two red lines divide the plane into four parts. A dot in the upper left section indicates an East Asian economy that during a certain five-year period grew at a rate above 6% when its per capita GDP was below 40% of the US level.

Although China’s extraordinary economic growth is mainly driven by internal factors. trade and foreign investment have been the enablers of the internal forces, without which China’s technological catch-up would have been much slower. Therefore, maintaining an open economy is still the best policy for China even if some countries may choose to become less open. China can afford to be more open than before as the country is already at a stage where its companies can successfully compete with their foreign counterparts on a level playing field.

Investment has a greater impact on economy

It is worth noting that domestic demand involves not only consumption but also investment – the latter of which actually has a greater impact on economy.

Investment is much more cyclical than consumption. An economy overheats as a result of overheated investment and stagnates mainly due to sluggish investment, resulting in sluggish consumption. As such, consumer demand should not take the blame for decelerated economic growth in China, and nor should we count on short-term policies to substantially boost consumer demand. In fact, it is the investment demand – not consumption – that has suffered the fastest fall in recent years.

When an economy fluctuates sharply, consumption is relatively stable with basic living needs largely unchanged. The government may introduce policies to stimulate consumption of some non-essential or non-urgent purchases. These micro-level policies may work to some degree, but can hardly have a substantial impact on the macro-economy.

In terms of investment, private sector investment deserves the highest attention since, when it declines, a sluggish economy often follows. To bolster China’s private investment, it is important to create a positive business environment supported by more consistent and stable policies. The government may focus on fostering investor confidence and sense of security of property rights, while avoiding intervening too much in daily operations of private companies.

The best days of China’s economy are still ahead of us as long as it can avoid self-inflicted setbacks and firmly push reform and opening-up forward.

Zhu Tian is the Santander Chair in Economics at CEIBS. For more on his teaching and research interests, please visit his faculty profile here.