Helping policymakers draw a line between economic growth and environmental protection

By Zhang Shuang and Koichiro Ito

In a recent study conducted in China, we found that, over the last decade, awareness of environmental issues and rising disposable incomes means that consumers are now willing to pay for clean air.

Our research looked at air filter sales, pollution data and other related variables to illustrate how much consumers in particular regions of China are willing to pay for clean air and on what basis.

A detailed analysis of all available data revealed that, on average, people were willing to pay around 36 RMB to remove one microgram per cubic metre of pollution from the air, over five years. However, the exact amount from person to person varied considerably depending on several factors, particularly household income.

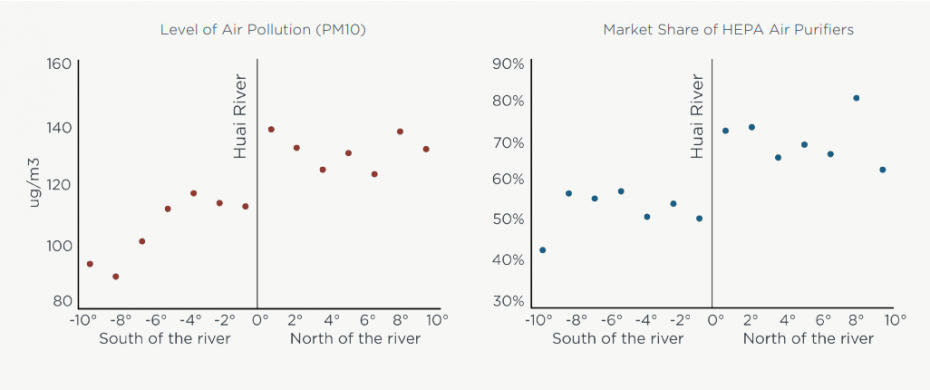

One of the key features of our study was its ability to capitalise on a side effect of a long-standing policy in China applied to households north of the Huai River (which runs from east to west, passing through densely-populated Anhui and Jiangsu provinces and which forms a geographic line which is customarily used to define “Northern” and “Southern” China). The government gives free heating generated from coal to locations north of this river. This keeps homes in the north warm, but creates around 30% more air pollution, compared with areas south of the line.

At the same time, other policies discourage mobility in this region, meaning people in this area have been constantly exposed to pollution for decades. Conversely, the fact such policy does not exist south of the river, makes the population in the south a good comparison group for the purposes of our research into the issue. The significance of this is that, in all ways we believe were relevant to the study, both groups, north and south, were the same except one was living in an area with a policy contributing to pollution.

As part of our study, we looked at sales data from the Chinese air purifier market from 2006 to 2014, covering some 690 types of products, over some 81 cities in north and south China, and compared this with pollution and demographic data for these areas. The results showed a strong correlation between air filter sales and level of pollution (see graph below).

Our findings are significant for policy makers in helping them determine which policies have the most relevant impact. Official data shows that annual average exposure to fine particulate matter in China is five times higher than in the United States, and policy makers and economists consider air pollution to be one of the first-order obstacles to economic development. Against this backdrop, the Chinese government and the World Bank worked together in 2005 to overhaul the Huai River policy which was widely considered to have become outdated.

As China’s economy developed, so did consumers’ relationship with the state and what they looked for it to provide. Those living north of the Huai River have gradually taken more responsibility for heating their homes. Previously, residents would simply be provided with heat from a central source and had limited control over how much of this resource they used regardless of how much they needed or what temperature they regarded as comfortable. The World Bank and Chinese government came up with a metering system to give consumers the ability to control how much heat they used and, in turn, an incentive to use less. From studying data related to policy change, we found that the willingness to pay for these reforms is around 12 million RMB per city per year – a figure which covers all known benefits of the reforms for all households. With the calculated cost of the reforms standing at around 86,000 RMB per city per year, the cost benefit analysis is clear, and suggests our study may be a useful indicator for governments when deciding where to draw the line between economic growth and environmental protection.

This study originally appeared in the Journal of Political Economy here. Zhang Shuang is a Professor of Economics at CEIBS. For more on her teaching and research interests, please visit her faculty profile here. Koichiro Ito is an Assistant Professor at the University of Chicago.