Engaging with Startups to Drive Corporate Innovation

During a presentation at the Huawei-hosted Innovation Roundtable, attended by 160-200 innovation executives, Dr. Ramakrishna Velamuri, Chengwei Ventures Chair Professor of Entrepreneurship at China Europe International Business School (CEIBS) provides a broad categorization of the tools available to corporations to achieve their innovation objectives. He then focuses on the different ways a corporation can engage with startups to create a symbiotic relationship. Here are excerpts from his presentation.

Startups are Driving R&D and Innovation

In the 1950’s and 1960’s, government labs were the primary drivers of R&D. During subsequent decades, large corporations took over and became the dominant R&D spenders. In the last 15 to 20 years, SMEs have become hotbeds for innovation. This is demonstrated by research conducted by the National Science Foundation, which verifies that SMEs that are research active tend to dedicate a significantly higher percentage of their revenues to R&D than large corporations. They also employ more scientists and engineers as a percentage of their workforce.

Prof. Velamuri sums up some of the key drivers that have empowered startups to become major sources of innovation:

- The move from capital expenditure to operating expenses for server capacity, manufacturing, and logistics is making it easier for startups to operate without substantial capital burdens. Furthermore, drastic price reductions on technologies such as sensors and industrial robots have created a market through which such tools are very much within the reach of entrepreneurial companies

- Another significant trend is the proliferation of financial resources for young, innovative organizations. For example, from 2005 to 2012, the number of venture capital firms in China increased from 500 to 6,000. This means that entrepreneurs don’t have major barriers in terms of capital availability

- The emergence of support services such as incubators and accelerators helps startups gain speed to market, while also helping them scale

- In emerging markets, there are more and more first generation entrepreneurs, i.e., who don’t come from “business families”. While these youngsters may not have either the social or the financial capital of a business family, they are able to benefit from other strengths through their educational background and hard work.

Corporate-Startup Collaboration

Typically, large corporations are very slow, lack creativity, and are excessively process-driven. Oftentimes, they are much too focused on exploiting existing opportunities, which diminishes their ability to explore new ones. On the other hand, startups also face major challenges. Many of them have difficulties accessing new markets, gaining visibility, and establishing their legitimacy. At a certain point, they will look to scale, but find themselves with difficulties doing so given their limited resources. Looking at such challenges from the entrepreneurial and corporate perspectives, it is apparent that they have the ability to complement each other extremely well.

“[Corporate-startup collaboration] is quite challenging because you are talking about two very different cultures. The entrepreneurial culture versus the administrative culture of large organizations. The strategic orientation of the entrepreneur is the pursuit of opportunities, whereas executives from larger companies are more focused on optimizing resources that they currently control”

Engaging with Startups

Prior to engaging with startups, companies should look to gain clarity on three key issues[1]:

- It is vital to assess whether the corporation has the ability to screen and monitor a large number of startups

- Good startups typically have many suitors, necessitating the need to be clear about what the corporation’s distinctive value proposition, as a large firm, is to a startup – beyond what independent VCs, incubators, and accelerators can offer

- Corporations need to be very clear about their objectives in working with startups.

“Articulating a win-win value proposition is the first step. The second step, which is actually quite complicated, is setting up a good interface unit”

An interface unit, regardless of whether startup collaboration is equity-based or not, is truly critical. In setting up the right interface, companies need to be aware that within corporations with large workforces of several tens of thousand employees, such a team is likely to be very small in the grand scheme of things. It is therefore all the more important for the unit to be empowered. If you are a multinational company, Prof. Velamuri recommends taking a decentralized approach — in that there should be local units working with startups where they reside geographically.

Prof. Velamuri is an advocate of companies building a reputation for being startup-friendly organizations. This is ideally done by communicating stories about companies that you have collaborated with and the success gained from doing so.

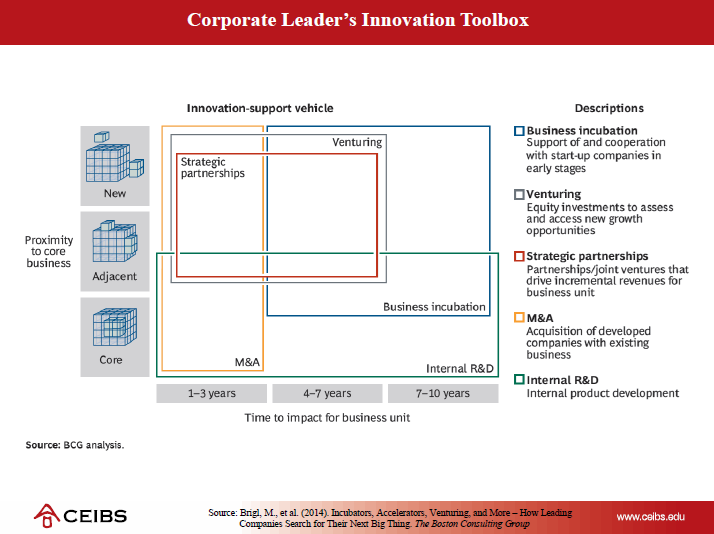

The Corporate Innovation Leader’s Toolbox

For the core business, corporate innovation leaders can basically make use of two instruments for innovation: internal R&D and M&As. When looking at areas that are considered adjacencies or outside the core business, on the other hand, there are fundamentally three mechanisms companies can make use of: business incubation, corporate venturing (which differs from M&As in that equity ownership is typically below 20%), and strategic partnerships.[2] With the latter primarily concerning itself with partnerships between parties of the same size, Prof. Velamuri focuses on the other two.

Corporate incubation programs typically revolve around collaborating with early-stage startups. While there is typically some equity investment involved, this doesn’t have to be the case. Incubation periods normally vary between 12 to 36 months. In corporate accelerators, companies will be working with startups that are much more developed than in incubators. The time frame of such an acceleration program is also much shorter.

There are many different types of incubation and acceleration[3]. The first one is called the inside-out model. Such a model has been applied for decades, with Xerox PARC, the R&D division of Xerox, possibly being the most celebrated. Typically, a corporate R&D lab has developed a technology considered to be non-core; yet, it could still hold considerable market value. Rather than just killing the technology, companies spin it off. The next model is characterized as being outside-in, wherein corporations look to engage with a large number of startups through a separate unit dedicated to the interface. With the admission of startups being open in this model, one way to attract startups could be by conducting a competition.

Corporate Venture Capital is characterized as being a systematic program of investing in early-stage companies. Corporations look to support startups with capital in exchange for equity shares – often 20% or less. There is a lengthy timeframe before one begins to see results in corporate venturing, often between five to seven years.

What do corporate venturing units such as Intel Ventures and BASF ventures contribute to startups? Besides funding, they contribute with endorsement through a reputed organization as well as provide startups with access to complementary resources and capabilities. In particular, the latter is unique to corporate venturing entities.

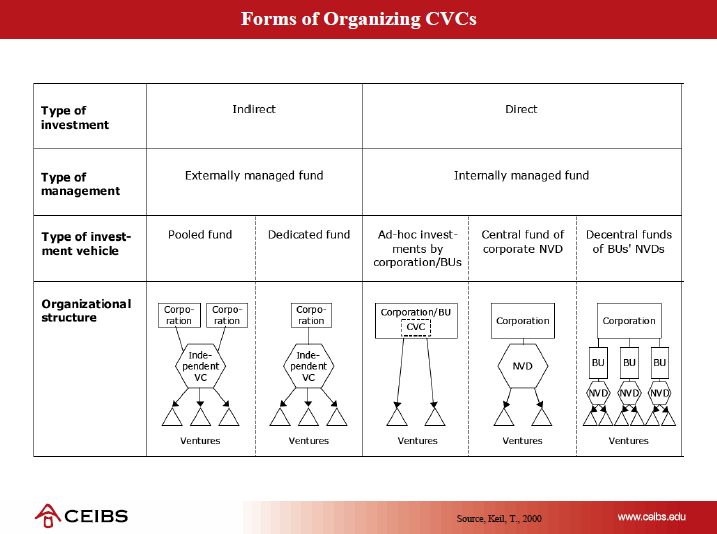

There are basically two forms of organizing corporate venturing[4]. One is an externally managed fund, where a corporation creates a separate legal entity that functions like an independent VC. In such a program, there will be fixed corporate funding commitments, making independent investment decisions to achieve a blend of strategic and financial objectives for the capital provider. Typically, people working in such an entity will predominantly have investment backgrounds, as opposed to employees with operational experience, generally seen in larger corporations. The other type is an internally managed fund. This refers to corporations’ practice of investing in startups directly from their own balance sheets. The model appropriate for any given company depends on what they want to achieve. If a company is interested in exploring new areas away from their core area, an externally managed fund might be more suitable. If a company is interested in finding startups within its core business/adjacencies, an internal model might be more appropriate.

“When it comes to CVCs, internal units are preferable when the near-term strategic goals are clear, and external units are preferable when you want to explore more disruptive technologies”

Prof. Velamuri highlights that corporate venturing programs are excellent tools when they are combined with other mechanisms, such as internal R&D, M&As, strategic alliances, and incubation.

“It works as a toolbox, just as a handyman has a toolbox, a screwdriver, a drill, and a hammer — you need to think about which tool is most appropriate for which situation.”

10 Lessons for Corporate Executives & Managers[5]

In conclusion, Prof. Velamuri sums up how to collaborate with startups with ten key takeaways:

- Carefully consider your objectives to engage with startups

- Select the program(s) that best deliver on these objectives

- Secure board-level sponsorship

- Develop key performance indicators

- Capture data and feedback continuously to iterate the model

- Hand startup programs over to people with an entrepreneurial mindset

- Allocate an internal champion with decisions and budget power

- Create a publicly visible, single access point for startups

- Scout internationally to attract the best startups and technology

- Make it easier for startups to work with you.

Q&A

How do you distinguish between the functions of the interface unit for startup engagement versus the corporate venturing team?

Typically, these are completely separate units. The corporate venture capital team is focused on investments, whereas the team that engages with startups, potentially through incubation or acceleration, is made up of people with strong operational backgrounds. These people would also be able to connect startups to the right internal resources within an organization.

Key Takeaways

- The complementary benefits in collaboration between incumbents and startups are pretty obvious. Corporations are typically slow, lack creativity, are too process-driven, and too focused on exploiting the existing business. On the other hand, startups usually have difficulty accessing new markets, gaining visibility, establishing their legitimacy, and have difficulty scaling. Both parties have distinct abilities in terms of assisting the other with shortcomings

- A prerequisite is to have an empowered interface unit attending to collaborations with startups.

- Build a reputation for being a startup-friendly organization by communicating success stories in terms of how startups have benefited from collaboration

- Tools such as internal R&D, M&As, strategic alliances, incubation & acceleration, and corporate venturing are comparable to a handyman’s toolbox — thought needs to be put into which tool is most appropriate for which specific situation.

[1] This section draws on Weiblen, T., & Chesbrough, H. W. (2015). Engaging with startups to enhance corporate innovation. California Management Review, 57(2), 66-90.

[2] This section draws on Brigl, M., Roos, A., Schmieg, F., & Watten, D. (2014). Incubators, Accelerators, Venturing, and More: How Leading Companies Search for Their Next Big Thing. Winning with Growth Series, Boston Consulting Group.

[3] See footnote 1

[4] Asel, P., Park, H. D., & Velamuri, S. R. (2015). Creating Values through Corporate Venture Capital Programs: The Choice between Internal and External Fund Structures. The Journal of Private Equity, 63-72.

[5] The ten lessons are taken from Mocker, V., Bielli, S., & Haley, C. (2015). Winning Together: A Guide to Successful Corporate–Startup Collaborations.