Building a “2R” supply chain in a global supply network

By Zhao Xiande and Wang Liang

The world economy is under great pressure due to the outbreak of COVID-19, and the situation may turn out to be a big wake-up call for global supply chain management (GSCM). Over the past three decades, despite some setbacks, supply chains in most industries have seen increasing global divisions of labour, which also explains why COVID-19 is having such a big impact on global supply chains. So, what changes will happen in global supply chains after COVID-19? And, how should we respond to these changes?

Highly integrated global supply chains: the ripple effect of COVID-19

In the context of economic globalisation, global industrial chains have become more diversified and integrated. Today a supply chain may involve dozens of countries and hundreds of companies, from raw materials to parts and components, to work in progress and eventually to finished goods. Such structures may lead to what we call the ‘ripple effect’ (i.e., a disruption) which, rather than remaining localised or being limited to one part of the supply chain, spreads and impacts the operations and performance of the whole supply chain.

‘Ripple effect’ describes the propagation of amplified disruptions in supply chains. A ripple effect occurs when the disruption of one part (Part A) of the supply chain causes the disruption of the other parts, which in turn hinders the recovery of Part A, and ultimately the whole supply chain gets bogged down.

Take the automotive industry as an example. Since the outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020, the ripple effect has diffused from China to global supply chains in three main stages.

Stage 1

Wuhan’s lockdown forced auto companies and auto parts suppliers in the city to shut down their manufacturing facilities. Auto companies across China then delayed restarting production after the Lunar New Year holiday due to shortages of supply.

Stage 2

Overseas auto companies and auto parts suppliers were affected by the disruptions in China.

Stage 3

As COVID-19 turned into a pandemic, major automotive industry clusters in Europe, North America, Japan and South Korea were seriously disrupted, which in turn hindered the automotive industry in China from fully resuming production, and the whole chain got bogged down.

For better or for worse, all parts of the supply chain are bound together. No one is an island. In the context of a global division of labour, how can companies learn from the COVID-19 crisis and improve their risk management by building a flexible, reliable and shockproof supply networks?

From operational thinking to strategic thinking: mind-set shift is a prerequisite for supply chain restructuring

Over the past few decades, many executives did not attach enough importance to supply chain management, considering it to be just an operational matter. Now, more and more executives are changing their minds and beginning to reconsider the role of the supply chain in building a sustainable competitive advantage. The supply chain is not just an operational issue anymore, but an important part of strategy and business model innovation. This mind-set shift is a prerequisite for successful supply chain restructuring.

One lesson we can learn from the COVID-19 crisis is that, in supply chain design, we should consider not only quality and efficiency (as we did in the past), but also risk management. A supply chain with sufficient risk management capability (i.e. the ability to address both demand and supply uncertainties) is a “2R” supply chain – responsive and resilient. Specifically, a “2R” supply chain is able to respond quickly and accurately to fast changing customer demands and market needs, and recover quickly from the disruptions due to the impact of external disasters, maintaining operations continuity to the greatest extent possible.

Five capability modules for a “2R” supply chain

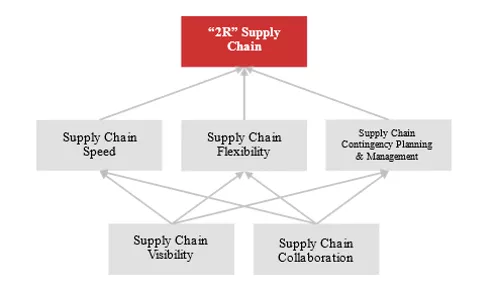

Successful cases of supply chain management show that there are five capability modules that companies should build if they want to make their supply chains responsive and resilient – namely, speed, flexibility, contingency planning and management, visibility, and collaboration.

Supply chain visibility is the ability to ensure that all stakeholders along the supply chain have access to timely and accurate information critical for their operations and thus can use the information to create business value. It is not just about technology. Many companies have the technical capability to establish internal connectivity, but find it difficult to achieve an end-to-end connected supply chain when it comes to inter-organisational connections. This highlights the importance of the “collaboration” module.

Supply chain collaboration refers to the close co-operation of all supply chain members driven by a shared goal in order to create more value than they could do individually. Since a company cannot do everything on its own, it needs to co-operate with others and leverage their resources and capabilities. How well it can do this largely depends on the effectiveness of supply chain collaboration.

Supply chain speed indicates the flow time of a supply chain, which can be improved by reducing lead time of key processes or eliminating non-essential processes through integration and innovation. Supply chain flexibility emphasises the ability of a supply chain to respond to and adapt to changes in demand (including changes in volume, product specifications and product variety). Supply chain contingency planning and management means that a company develops supply chain contingency plans for various crisis scenarios and, when a crisis actually occurs, executes the plans effectively and efficiently through cross-functional collaboration in the organisation. Such planning involves maintaining the proper level of “redundancy”, for example safe stock, backup suppliers, for unexpected situations.

It seems that end-to-end supply chain visibility and supply chain collaboration are the basis. They can help build and improve the other three modules. The establishment and integration of the five modules is largely based on digital technologies and big data analytics, especially the latter. Many executives used to rely on experience-based decision making, which tends to be inefficient in an emergency, due to a lack of relevant experience and an inability to leverage resources and capabilities of every part of the supply chain. Instead of relying on experience, executives should make full use of data from multiple parts of the supply chain through supply chain visibility and collaboration, so as to make supply chain decisions more quickly and accurately in the face of emergencies such as COVID-19.

Fig. 1: The five capability modules for a “2R” supply chain

Supply chain practices in the wake of COVID-19

A number of companies found their weaknesses in some of the capability modules during the COVID-19 crisis. A good example is the supply chain visibility in the automotive industry. Many auto companies realised that their data tracking was limited to first-tier suppliers, although most supply chains consisted of four tiers or even more. The “invisible” supplier data could be a major pitfall given the demand and supply uncertainties – compared with predictable risks, such hidden weak links that may be broken unexpectedly are often more fatal to a supply chain. As a result, the companies, suffering from poor data tracking, can only respond passively to the possible disruptions and always act in a flurry. Fortunately, there are still some companies adopting best practices in response to the COVID-19 crisis.

During a recent online sharing session on supply chain management under COVID-19, three CEIBS alumni were invited as panellists to share their insights and experiences. One of them was Stefano Tiziani, Head of Asia Procurement at Whirlpool and a Global EMBA 2019 student. Whirlpool is a leading major home appliances company, with 59 manufacturing and technology research centres around the world. The company has a multi-tier supply chain consisting of a large number of suppliers. According to Mr. Tiziani, Whirlpool established supply chain visibility through an online-based real-time sharing and tracking system, which allowed the company to make contingency plans and, with real-time adjustments, respond to emergency situations (e.g. COVID-19) quickly.

Another panellist was Damon Gu, Global Head of e-Commerce Logistics, Maersk Logistics & Services and a graduate of Global EMBA 2015. Maersk has a vast network covering over 300 ports in more than 120 countries. Its visibility solution can provide end-to-end transparency to milestone, status and performance of the supply chain and its partners, facilitating more timely and more effective business adjustments. During the recent period under COVID-19, the e-commerce logistics team at Maersk began acting as a shipping courier for a large number of Chinese customers, based on its global network and product innovation. In the process, it has become one of the most welcomed cross-border e-commerce export logistics solution in the market.

How well a company can co-operate with others in its supply chain and leverage their resources and capabilities largely depends on the effectiveness of supply chain collaboration. In the panel discussion, Eddie Huang, Associate CEO, SF Express, explained the supply chain collaboration practices adopted by his company. In the early stage of the COVID-19 outbreak, SF Express, just like other logistics service providers, suffered a serious capacity shortage in road transportation (e.g. a lack of truck drivers). In response to the challenge, the company managed to build a “shared and open” social capacity pool. The social capacities, along with the company’s own cargo aircraft fleet and warehouse network, contributed to a reliable logistics network.

The two basic modules, supply chain visibility and collaboration, are complementary and mutually reinforcing, supported by digital technologies. It is desirable that executives seeking to lay a solid foundation for a “2R” supply chain take all these factors into account. A chain is only as strong as its weakest link.

Digital technology is instrumental in improving supply chain collaboration, but it doesn’t play a decisive role. More important factors include the selection of supply chain partners, design of co-operation and revenue sharing mechanisms, and supply chain relationship management. Indeed, a particularly important factor about supply chain partners is the willingness to co-operate and their level of commitment to the relationship. Many executives focus too much on “hard” attributes such as costs and capabilities, while ignoring those relatively “soft” but very important attributes. In the face of a crisis, however, a tier-B supplier that is willing to do its best for you may be more valuable than a tier-A supplier that does not attach much importance to you. Therefore, executives need to rethink and adjust their selection criteria and mutual development strategies for supply chain partners.

Suggestions for executives

Enthusiasm for centralised sourcing and cost advantage in supply chain management is cooling down. More importance is being attached to the localisation of suppliers and the compatibility of supply chain infrastructure. Digital supply chain transformation is accelerating and greater emphasis is being placed on omni-channel and home delivery service. The ability to address last mile delivery challenges is becoming more and more important.

All these trends both call for and facilitate the optimisation of supply chains, which is by no means easy. Executives should review their supply chain strategies, plans and action programs, and start the journey of supply chain improvement and restructuring as soon as possible.

Here are six suggestions:

- Adopt digital technologies to improve end-to-end visibility of the supply chain.

- Apply big data analytics and AI to automate and optimise supply chain processes and decisions.

- Enhance supply chain collaboration through relationship management and supplier selection.

- Redesign the supply chain network and map the processes in the network.

- Follow the changes in consumer demand and improve customer satisfaction through an omni-channel supply chain.

- Establish a supply chain risk management function, make contingency plans, and maintain the proper level of “redundancy” with balanced consideration of risks and efficiency.

Zhao Xiande is the JD.COM Chair in Operations and Supply Chain Management at CEIBS for more on his teaching and research interests, please visit his faculty profile here. Wang Liang is a research fellow at CEIBS.