"America First" or "America Alone" - How should countries respond to ever-changing US tariffs?

By Bala Ramasamy and Mathew Yeung

“Liberation Day” on April 2, 2025, did not provide any kind of clarity on America’s long-term strategy for imposing tariffs and “rebalancing” US trade relations. Neither did the end of the 90-day pause, as July 9 came and went. A third resumption was scheduled for August 1 only to see yet another round of pauses, exemptions and flurried renegotiations. At the time of writing (August 26, 2025) it’s anyone’s guess how, when, and by what magnitude the spirit of Liberation Day will be fully invoked.

A handful of countries have some form of seemingly stable agreement, including the UK, Vietnam, and most recently Indonesia, while several others have received their “trade letters” from the Trump Administration. US tariffs on Japan and South Korea for instance, currently stand at 15% while Malaysia is at 19%. Why these countries were offered more “lenient” treatment is unclear, as are the additional conditions and exemptions around transshipment from China. Conventional logic would imply that future agreements should follow the Vietnam model, i.e. a 40% tariff. Logic, however, is evidently not the first tool that the Trump Administration reaches for when determining the next phase of its tariff policy.

Given the volatility and speed of changes involved in current trade relations with the US, how much advantage can countries really expect to gain by continuously negotiating and renegotiating these tariffs with the White House? How much should countries be willing to give in to Mr. Trump’s demands, when long-term US adherence to any such settlement can clearly be derailed based on short-term political goals and priorities? A case in point: the additional 10% tariff that the President Trump has announced will be imposed on any country that aligns itself with the “anti-American policies of the BRICS group”.

Given such an uncertain US trade landscape, countries big and small may benefit from a more patient and unified approach, rather than rushing to Washington every time the Trump administration releases a new tariff chart.

Who needs whom more? The price of rearrangement

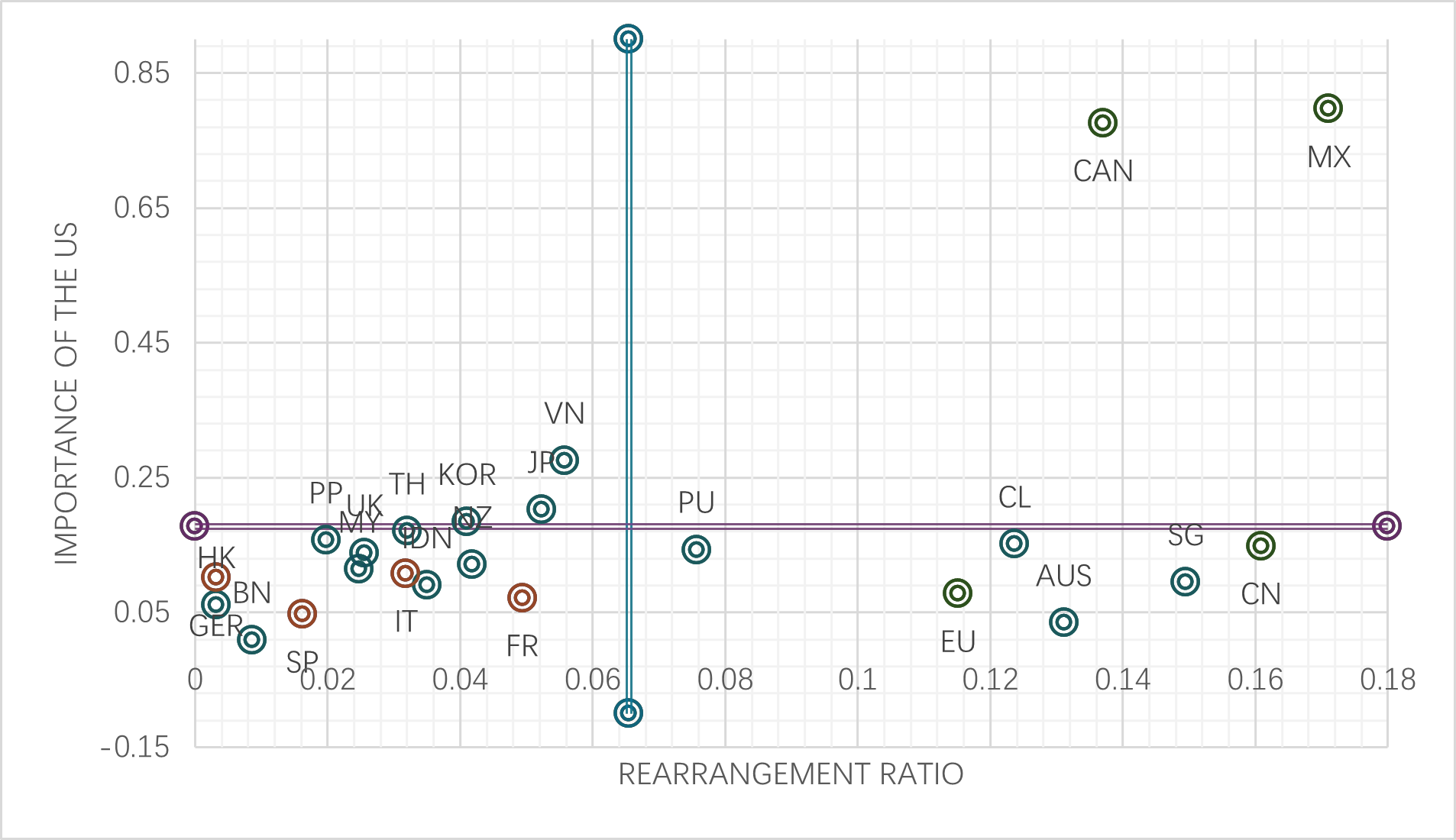

Recently, McKinsey published an article that highlights what they call the “rearrangement ratio”. This ratio is defined as “how readily a country might shift its imports from one trading partner to others” and is expressed as “the country’s imports from that trading partner as a share of the total available remaining global market”. A smaller ratio implies that the importing country has many other source countries (as well as its own domestic production) to replace its current imports from a specific trading partner. A good example offered by McKinsey is Christmas decorations. The US imports $3 billion worth of these decorations from China, while global exports (excluding China’s exports) to the US constitutes a mere $600 million. Given that the US produces very few Christmas decorations, the rearrangement ratio would be very small, indicating that US retailers would find it difficult to replace Chinese suppliers with other sources that can manage comparable scale.

After calculating these rearrangement ratios for 5,000 product categories, and averaging them across all products, the chart below presents these ratios (horizontal axis) on a canvass with respect to the importance of the US market to the country (vertical axis).

Re-arrangement Ratio vs Importance of US Market

AUS Australia; BN Brunei; CAN Canada; CL Chile; CN China; EU European Union; FR France; GER Germany; HK Hong Kong SAR; IDN Indonesia; IT Italy; JP Japan; KOR South Korea; MX Mexico; NZ New Zealand; PP Philippines; PU Papua New Guinea; SG Singapore; SP Spain; TH Thailand; UK United Kingdom; VN Vietnam.

The top left quadrant represents countries with the weakest bargaining power, as they value the US as an important market, and their products can be easily replaced from another source by US importers. It’s unsurprising, then, that Vietnam was among the first governments to send a delegation to meet the Trump team. The governments of Japan and South Korea did well by re-negotiating their tariffs down from 25% to 15%. Thailand and the Philippines should also consider “bending the knee” a little to ensure a favourable deal, given that their past alliances with the US may no longer be sufficient in the Trump era.

Countries in the lower right-hand quadrant have the most enviable position and probably have the highest negotiating power. Australia, the EU, Singapore, China and Chile have a relatively high rearrangement ratio, but the US market is not extremely important to them. Chile provides an instructive example, as it recently challenged America’s 50% tariff on copper knowing full well that the US has few alternatives to satisfy their demand; there is a high likelihood, therefore, that a large portion of the imposed tariff will ultimately be paid by US consumers.

The economies in the bottom left quadrant would perhaps find it more useful to consider diversifying their market away from the US to other markets like the EU. This may be tough, given the economic environment in Europe, but would at least provide companies from Malaysia, Indonesia, Hong Kong SAR and New Zealand some time and room to manoeuvre. A deal with the US will surely be one-sided. The recent deal with Indonesia announced by Mr. Trump clearly favours the US, for example. As for Hong Kong SAR, its future will be more strongly impacted by its evolving relationship with mainland China.

Finally, we have the two extreme cases of Canada and Mexico. Both countries are markedly smaller than the US, but cross-border trade among neighbours is natural. Both countries are capable of staying their current course and insisting on fairer rates, as US importers will have a difficult time finding alternative sources.

The China context – Next moves in the tariff game

Now let’s focus on the specific case of China. Its position of relative strength (lower US market importance, high rearrangement cost for US importers) provides crucial context for understanding its response to the various levels of threatened US tariffs.

China did not rush to DC for talks during the opening salvo of tariff threats, which ultimately reached a peak of 140%, correctly guessing that such posturing was designed more for PR purposes rather than actual policy. Instead, China preferred to meet halfway in Switzerland and later, London, to quietly negotiate tariff terms. Currently, average US tariffs on Chinese exports now stand at 57.6%, while China's average tariffs on US exports stand at 32.6%.

In light of the McKinsey analysis, several realities and subsequent strategic suggestions stand out in China’s case:

- On balance, the US needs Chinese imports far more than China needs the US market.

- Like China, the EU, Australia, Mexico, Canada all have high negotiating power (albeit in different forms) to resist punitive US tariffs.

- Accordingly, China should pursue closer ties with these countries in an effort to negate the “divide and conquer” strategy that Trump clearly favours.

- A united front, backed by more favourable trading terms between China and said countries, can only weaken this strategy further if the US struggles to find viable alternatives for Chinese exports.

- Chinese enterprises may have more bargaining power and resilience than perhaps they even realise. While a blanket tariff may be imposed on their industry, Chinese enterprises can work with US importers to determine a more equitable arrangement of who pays for it. A 30% tariff, for example, could be managed as a 10/10/10 split between the Chinese exporter, the US importer and the US consumer in the form of a higher commercial price point.

Standing firm may be the cheaper long-term option

Trade wars hurt everybody, by varying amounts and for different durations. The ultimate determinant of the outcome is always the same: who needs whom more?

As shown in the chart above, countries targeted by US tariffs spreads across a wide spectrum. Accordingly, from his perspective the “divide and conquer” strategy of Mr.Trump makes perfect sense, and any counterstrategies to deal with inevitable “tariff tantrums” will have to vary by country.

More widely, however, logic dictates that the best way to respond to US tariffs is to create a united front, so that “America First” ultimately translates to “America Alone”. Ignore the frantic headlines and eye-catching tariff rates: the inescapable reality is that the US cannot survive without imports. American consumer appetites are simply too large and too broad for domestic producers alone to satisfy. This is a US economic weakness that the rest of the world would do well to exploit at the negotiating table, particularly those countries that sit on the right-hand side of the chart.

Bala Ramasamy is Associate Dean and Professor of Economics at China Europe International Business School. Mathew Yeung is Dean of School of Open Learning and Associate Professor of Marketing at the Lee Shau Kee School of Business and Administration, Hong Kong Metropolitan University.